What do you know about your bones? SwRI is developing artificial intelligence (AI) for enhanced bone imaging to give patients a clearer picture of bone health. Current imaging methods, such as CT scans, protect patients from excess radiation but don’t provide detailed information on bone structure. SwRI technology runs these existing images through AI to fill in the blanks on bone health. The AI produces higher-resolution bone images with no additional radiation. Healthcare providers get a better picture of fracture and osteoporosis risk. Patients get faster intervention.

Listen now as Dr. Lance Frazer, SwRI biomechanical engineer, discusses the benefits of artificial intelligence for bone imaging and shares his top research-backed tip to strengthen our adaptable, living, smart bones.

Visit Bone & Biomechanics to learn more about SwRI’s bone modeling and analysis.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of the episode, modified for clarity.

Lisa Peña (LP): Artificial Intelligence is revolutionizing health care, and now SWRI researchers are using AI to combat osteoporosis, characterized by weak, brittle bones. How a cutting edge AI image of your bones could more accurately assess if you are at risk for osteoporosis and bone fracture-- that's next on this episode of Technology Today.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We live with technology, science, engineering, and the results of innovative research every day. Now, let's understand it better. You're listening to the Technology Today Podcast presented by Southwest Research Institute. From deep sea to deep space, we develop solutions to benefit humankind. Transcript and photos for this episode and all episodes are available at podcast.swri.org. Share the podcast and hit that subscribe button on your favorite podcast platform.

Hello, and welcome to Technology Today. I'm Lisa Peña. Osteoporosis weakens bones, making them prone to breaks. Many people don't know they have osteoporosis until they experience a fracture. In some cases, the break can be life-threatening. Current methods of assessing fracture risk lack clarity and accuracy. That's where artificial intelligence can intervene for a better picture of bone health. Our guest today is SWRI biomechanical engineer Dr. Lance Frazier. His team is developing AI to assess osteoporosis and fracture risk. Thank you for joining us, Lance.

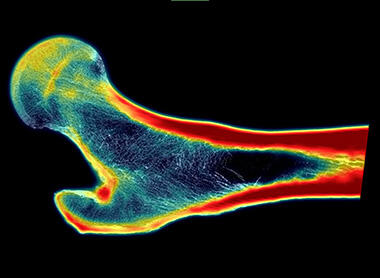

Image

SwRI’s super-resolution technology, which uses artificial intelligence to create higher-resolution images from CT scans, produced this image of the femur microstructure. Clear images like this could help physicians better assess osteoporosis and fracture risk in patients.

Lance Frazier (LF): Thank you for having me.

LP: So, bone loss and bone fracture caused by osteoporosis can have devastating consequences. And your team is looking for a more accurate way to answer the question, If you fall, will you break your hip or another bone? So we'll get into that in just a moment, but I want to start with understanding osteoporosis. We know it is a disease characterized by bone loss, but how does that happen? What are some common symptoms, and who is most at risk?

LF: OK, we'll try to cover all of that. So, many people do know this, but bones are living tissues, and they are constantly adapting. We call that process remodeling.

So bones are always getting stronger through formation, and they're also at the same time getting weaker transiently through a process called remodeling. And what ends up happening is you have this nice balance. You build new bone. You resorb away damaged bone, and you have this nice sort of symphony going on throughout your life.

As you get older, that balance can shift, and you start to build less bone, but you're breaking away more bone. So the balance shifts. In general, that's kind of the cause of osteoporosis.

A couple of questions you asked there-- who is most at risk? Because that balance is so in tune with hormones, women are especially susceptible. And as they age and as their hormone profiles change rapidly, that can have a significant shift in that balance we talked about.

LP: Are there common symptoms of osteoporosis? Like, how do I know if I have it?

LF: Yeah, so they call osteoporosis a silent disease. It's really challenging to wake up one day and go, oh, you know what I have an osteoporotic symptom. And so that's why it's often a pretty nasty disease because you don't know you have it until you have a pretty bad fracture.

Some things that can clue you in, I suppose, without actually getting a formal diagnosis. Some people do complain a little bit about losing height. And that can happen because you can have minor compression fractures in the spine that you actually don't really know are there, and they cause you to shrink a little bit. But you can also shrink because of soft tissues in between your bones.

So that's a tough one. You might stoop a little bit. Maybe your spine becomes a little bit more rounded, and you start to notice that. Possibly back pain-- maybe you have minor fractures from things that really shouldn't be breaking bones. But all in all, it's called a silent disease for a reason.

LP: And you mentioned women being in a higher risk group, but age plays a factor. What is that key age that you're looking at when you're thinking of osteoporosis?

LF: Yeah, we usually look at age as once you reach over 50 is when risk really starts to elevate for a lot of people. And then when you get above 65, things really become risky.

LP: OK, so I think great explanation. Thank you for clarifying that for us. Osteoporosis is when you are essentially losing bone faster than you are building it. So let's talk about why you are targeting osteoporosis for your research. What makes this an, I guess, ideal disease to combat with artificial intelligence?

LF: With artificial intelligence, yeah, it's a great question. Well, why are we targeting it? Our group and my team is looking at a lot of things related to health and injury prevention. And it turns out that bones are one of the most common injuries.

And so it's an easy place to start or an impactful place to start. When you're looking at things like health, health affects every single person. So you have this issue of throughput. You only have so many clinicians that can look at so many people.

Artificial intelligence really has no limit on how many people, so to speak, it can look at. It can do this stuff kind of instantly. So from just a throughput perspective, artificial intelligence makes a lot of sense in the health field, especially. And also, there's a lot of the technology required to really diagnose this stuff really comes down to imaging technology. And that's an area where artificial intelligence can just be so, so great.

One example is when you're getting an X-ray-like scan, if you get a DEXA or a CT scan in a clinic, you actually have to be exposed to a little bit of radiation for that to happen. And so you want to minimize the amount of radiation that you're exposed to, but you also want a really clear image. Well, with more radiation, you get a better image, but it's more harmful to the person.

Well, artificial intelligence can kind of aid there as well because we can and we'll get into this in the research. But artificial intelligence can improve image quality without having to sacrifice more radiation exposure. So high throughput, the ability to improve upon the technology that we already have, I think those two things really make bone health a good target for artificial intelligence.

LP: Okay, so let's take a step back a bit and look at how we are currently doing things surrounding osteoporosis. How is it currently diagnosed and how do health care providers determine if someone is at risk?

LF: So the gold standard for diagnosis is what's called a DEXA scan. And that's essentially just an X-ray. And so they can look at how much bone you have in key areas. And one of those key areas is the femoral neck-- basically, your hip.

So you get an X-ray. And if the image is really bright white, it means you've got a lot of bone there. And if it's pretty dark, you have less bone there. And we have standards on how we can sort of measure how much bone is there. And you just compare that to the average healthy adult, believe it or not.

You get your scan, and you say, well, you have less bone than the average healthy adult. We're going to label you as osteopenic, or you have a lot less bone. We're going to label you as osteoporotic. And that's kind of how the diagnosis is done.

LP: All right, so as much bone as a healthy adult, less, or a lot less. That's what we're talking about currently. So as you just mentioned, current methods provide some insight on bone health.

But your thought is, your team is thinking we can do better with artificial intelligence, AI. We are hearing a lot about AI these days in just about every field. So let's do a quick AI overview. What is it?

LF: What is AI? The age old question.

LP: Yes, what is AI? We are seeing we are seeing its uses really everywhere these days. I think most of us know what it is, but how do you describe it?

LF: Yeah, I think it depends on who you ask and what field they come from. They'll probably give you a slightly different answer. AI is a branch of computer science that involves trying to create systems, or machines that are capable of performing things that normally require human intelligence, things like learning, learning as in something happens, and the machine can actually learn from it and do better next time.

Reasoning being able to solve problems that normally require human thought. Perception being able to notice things that perhaps a human wouldn't be able to necessarily perceive unless they were truly focused on it. But I guess at the end of the day, it's teaching or it's creating machines and systems that can reason like a human would.

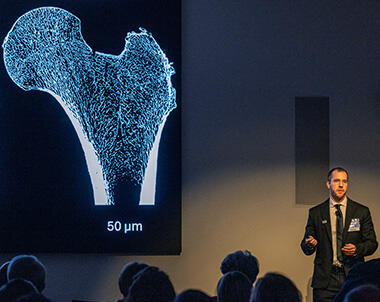

Image

Dr. Lance Frazer, SwRI biomechanical engineer, presented his research on AI and bone health at SwRI’s 77th Annual Meeting held February 17, 2025. A paper authored by Frazer and colleagues titled “Super-resolution of clinical CT: Revealing microarchitecture in whole bone clinical CT image data” appears in the journal Bone and is available here.

LP: Okay, so let's get into let's get a little bit more into your research. How can AI improve risk assessment for osteoporosis?

LF: Okay, so maybe I'll give a little bit of history of how we kind of stumbled into this, the current state of the art technology for CT imaging a lot of us are familiar with a CT scan. The technology has gotten pretty good in that, let's say, 20 years ago, if you were to get a CT scan of your bone, your bone would look pretty pixelated, and you can't make out any of the internal structure.

So if you saw a picture of a real bone, there's just an immense amount of internal structure. We call that the trabecular bone and the microstructure. You can't see any of that. It's just this pixelated mess.

Fast forward to today, CT scan technology has gotten pretty good where you can actually, with our again, with our human reasoning, we can look at that and say, I think there's a structure there. There's a pattern. I can see it, but I can't quite quantify in any meaningful way.

I just my brain knows it's there. So we saw some of this new age CT technology, and the side of biomechanics that my group really focuses on is all about computer modeling. And I'm going to be jumping around a little bit here, but it's going to come together.

So what we do is we can create physics-based models of anatomical tissues, and we can subject them to different types of scenarios and environments. So I can create a computer model of somebody's bone, and I can subjected to a fall, and I can say, will this bone break? Well, through that sort of skill set, if I really, really want an accurate picture of how strong that bone is and I want to model it correctly, I need to know what that microstructure looks like.

And we have tools to quantify it, and we have tools to embed that information into the model. So that's where we want it to get to. We say, OK, we want to make computer models of bones, but we need that microstructure.

And again, the CT technology is almost there to get us that microstructure, but it's not quite there. So then we had the idea of, well, why don't we just use AI to kind of push us across that line? If we can improve the image data just a little bit and we can see that microstructure, well, then I can make again, which was our original plan, I can make really accurate models quite easily of individuals' bones and subject them to all different types of loading and falls and actually quantify the risk of fracture. So that's kind of how all of this came together and how we got to where we're at today.

LP: Okay, so you took these CT scans, and you are pushing them through AI and getting a clearer picture.

LF: How we do this is we have, here at SWRI, what's called a micro CT scanner, and it can provide incredible resolution. And so we have a whole freezer full of bones.

LP: Just for clarity's sake, where do you get a freezer full of bones?

LF: Yeah, where do you get freezer full of bones? When people donate their bodies to science, people can do great things with them.

LP: Okay, so these are real human

LF: These are real human bones that we are the beneficiaries of receiving, and we are trying to better human health with them. So we are very appreciative that people donate their tissues to science. So we have a micro CT here.

This provides incredible resolution. You can see every single detail of the bone that you'd be interested in, at least for biomechanics. But you can't do that kind of a scan in a clinic.

The radiation that you subject these bones to is way, way, way too high. So it's not even on the table for clinical scans. But what we can do is we can take this freezer full of bones, image them here at the institute with our micro CT, and then also imaged those same bones on a clinical CT scanner.

And then we say, okay, here's a picture of a bone from a clinical CT scanner, and here's that same bone from a micro CT. And then you teach AI to look at that clinical scan and just improve its image quality to look like what it would have looked like had you scanned it with a micro CT. So you're teaching AI to take that clinical scan and essentially upgrade it to a micro CT scan that you cannot get in a clinic.

LP: And after it sees these images repeatedly like, this is the image we start with. But this is how clear we want it to be. It pretty much can do it itself. It takes over and is able to fill in the blanks itself.

LF: Yeah, and it requires a lot of what we call training data. So it did take a lot of scans and a lot of bones. And you need that data because you have to be very careful with medical image data.

You don't want the AI to hallucinate things, which is create an image that it really shouldn't create, or give you a picture of bone that really doesn't exist or is not even physiologically possible. So it does need to be accurate when you're dealing with medical stuff. So it took a lot of data, a lot of scans, to get it accurate. And we have a couple of metrics that we were looking at to make sure that the AI was producing an accurate picture of that particular bone.

LP: You end up with this astoundingly clear picture put out by AI of what a patient's bone looks like. So once a patient is identified as being at risk, what can be done? Will this expedite treatment?

LF: Yeah, so with something like and I think this is true for almost any medical diagnosis. Early identification is always, always best, and that's where the issue of osteoporosis really is. It is really difficult to catch early indications that somebody is down the path of osteoporosis.

So this type of technology hopefully will be able to identify it soon because not everybody and we haven't really talked about the difference between osteoporosis versus just fracture risk. But not everybody that's osteoporotic is at risk for a fracture. But to answer your question of what can be done, well, if you identify this stuff early enough, the number one thing is really just lifestyle modification because we mentioned this at the beginning.

Bones, they're adaptable. They're living. They're smart.

If you want to build bigger bones and stronger bones, you absolutely can with just lifestyle modifications. So that's weight bearing exercise, impact, sports, like, jogging. A lot of people here play pickleball. It's a great sport. Weightlifting is far and away the best thing you can do. Diet, sleep, sunlight, lifestyle modifications, far and away.

LP: All the good things they tell us to do anyway turns out are great for your bones to.

LF: There's a lot of wisdom there.

LP: Yeah. So I really like the way you described bones. I guess we don't really think about them very often, but adaptable, living, and smart.

LF: Yes.

LP: So a lot of great technology here in the works. So what stage of development is this AI in? How soon do you see this in doctors' offices helping patients assess bone fracture risk?

Image

Dr. Lance Frazer is a bone mechanics and machine learning expert. In addition to exploring AI for bone imaging, Frazer is developing human digital twin, human performance and military injury risk prediction technology.

LF: So this is a difficult one. I'm going to answer it in two different ways. So this technology where you improve image data, this is a known technique, and it's called super resolution, to actually put a name on it. So the artificial intelligence that we're using to improve image quality, it's called super resolution.

This is already being used in a lot of places and in a lot of different fields, and the makers of medical imaging technology, people that actually make CT scans, make MRI machines, they're well aware of super resolution. And this is going to be a thing if it already isn't a thing. So that, I would say, is going to be in doctors' offices now or tomorrow.

But the part of actually using this to assess osteoporosis and fracture risk, which is the really important thing that's a ways away. And the reason is in order to get that in a clinic and have it be actually used by clinicians, you have to do a lot of work. You have to have, clinical trials where you actually prove that the algorithm you're using does, in fact, identify people who are at risk, and you have to prove that the bone strength quantification you're putting on somebody is accurate.

And that takes a lot of work and a lot of testing and a lot of time. So to actually have that part in the clinic, there's a lot of work to be done. But just being able to have clear medical image data, we're there. And super resolution is really taking off, especially with AI in general just exploding. So, good and bad news I suppose there.

LP: Yeah, so it's coming. Might take some time, but we're getting there. So are you able to tell us what stage of development you're in? What's next for you as far as getting this into a doctor's office?

LF: Yeah, so we're still just trying to improve it. Right now, we can take I'm going to be hesitant to use actual numbers here. We can improve image resolution right now about six-fold.

So what that means is if I have I'm going to use numbers just for numbers' sake, but we can take clinical scans that have a resolution of what's called 300 microns. And the smaller that number is, the better. We can get that to 50.

So we can get a six-fold increase in the resolution. What we would really like to see is a 10-fold increase. And the reason is most clinical scans are not going to be at that 300 mark.

That is your new age CT scanner technology. Most scanners in the country are going to give you something like 500. So what you would like to do is go from 500 to 50.

And so we need that 10-fold increase. So we're just working on improving the super resolution capabilities, and we know how to do it. It just takes more bones, more data, more freezers, and we'll get there.

LP: More freezers full of bones. All right, so, really close it sounds like, and you're making those improvements every day. So, SWRI researchers are working on other health care applications for AI, including cancer and traumatic brain injury detection. So is your team looking into applying AI to other conditions outside of osteoporosis?

LF: The short answer? Absolutely. I get asked actually quite a bit how much AI do you work with on a day to day.

So when I went to school, I did not use AI for pretty much anything. I was strictly a computer modeling guy. I built physics-based models and did a lot of cool stuff with that.

I would say now, 10 years later, almost every project I'm involved in has AI in it. So what are some things we're using AI for? Well, the high level answer is we're trying to optimize human performance, whether that be sports or military or just civilian health in general. We're trying to prevent injuries in the civilian sector, the military, sports, all things just bettering the human experience as far as our bodies go. And in almost every aspect of that, AI is involved.

LP: Okay, we've touched on this a little bit, but I want to get a little bit more into it. Through your research, you've explored bone health. What can we do to build stronger bones? You mentioned all the good things, exercise. You know, what do you suggest to your friends and family?

LF: Yeah, disclaimer not medical advice. But I don't think there's a person in the world that would tell you not to exercise. Specifically for bone health, resistance exercise, weightlifting and weight bearing type exercises, there's actually a really interesting study that was done.

Researchers looked at pitchers, MLB pitchers, and they looked at their bones on their throwing arm versus their non-throwing arm. And on their throwing arm, those bones experience a tremendous amount of load. The muscle pull that's happening on those bones is really it's quite incredible.

So what they found was their pitching arms, their bones, were significantly bigger and stronger, and you actually see it on the image data. I mean, you had like a thick, thick bone on the throwing arm and then your just typical regular bone on your non-throwing arm. And that was just one cool example, but, I mean, we've known for a long time that you use your bones hard, you will build them stronger.

LP: What is the process that translates physical movement to bone health? You think of exercising, and you think of building muscles or losing fat. But you don't really think of it as contributing to bone structure.

LF: Yeah.

LP: How does that link?

LF: Yeah, that's a fun one. So I said bones are smart, and bones have little sensors in them, these little sensor cells. And they can detect when they're under a lot of mechanical stress.

And when that happens, those little sensors, they send out a signal that says, hey, we need to build stronger here because we're seeing a lot of stress in the same way that muscles adapt. They see a really high stress. They become damaged, they build back stronger.

Bones are the same way, and they can detect that high level of stress that's being exerted on them. And in fact, before I even got here, our group, my boss in particular, Dan Nicolella, he did a tremendous amount of work actually looking at those sensor cells and how they can really detect that mechanical environment and how that leads to a signal that says build back stronger. The other thing too, is bones are they're just designed in such a cool way.

So when you use them, they're being damaged continuously, and they form these little micro cracks. And in the same way that cells say, hey, we need to build back stronger, they also detect the damage. And the only way you really damage bones is by using them.

And so when you have that damage signal, what ends up happening is it says, first, let's heal this damage. And that's that dance I was saying where bone will resorb away. So it heals the damage, and it actually removes bone.

But then when it builds back, it builds back stronger. And so you have this cool dance that's going on. And again, as you age, that dance gets a little out of control, and you're taking away bone, but you're not really building it back. But yeah, it's all about the adaptability of our bones and how they can just sense what's going on. And they say, let's get stronger.

LP: So they bring in reinforcements.

LF: They bring them in.

LP: That's so cool.

LF: Yeah, it really is cool.

LP: Adaptable, living, and smart, as you said. Really, really interesting because, yeah, I wasn't aware of the bone sensors. So, really interesting.

OK, so I imagine you are living as you preach. Has your work your research, brought about lifestyle changes for you personally? What are you doing differently now that you know all of this?

LF: Yeah, it certainly has. My research definitely has influenced my lifestyle. I do try to regularly weightlift and do just in general cardio exercises to stay healthy.

But the thing is, even though we're talking about bone health, there is just so much good that happens in your body when you take care of it, you eat well, you exercise, you sleep well. And so absolutely, I'm aware of those things, and it has become a part of, of my lifestyle, for sure.

LP: Yeah, it's a full picture benefits there from living a healthy life. OK, so Lance, what do you enjoy about this work? Why is it important to you?

LF: Well, I love my job. I tell people that, and I genuinely mean it. All of us have bodies. So this is something that everybody can relate to. So it just makes it fun to talk about.

But because I'm learning about things that directly impact me, it really is enjoyable. I have what word am I looking for? I have skin in the game, so to speak, where I also have a body, of course, and I want to take care of it.

And researching this stuff and learning about how we can be healthier is really cool. And healthier and just also prevent injuries and just have a higher quality of life as we age because maybe it's not so much of how long you live but how many quality years did you have. And a lot of that comes down to how well you prevented injuries, how well you took care of yourself. And so it's a really cool field to be in, and I'm very fortunate that I'm in this field.

LP: All right, health is wealth, as they say.

LF: Health is wealth. You betcha.

LP: All right, your paper titled Super Resolution of Clinical CT Revealing Microarchitecture in Whole Bone Clinical CT Image Data has been published in the journal Bone. We will have a link to the study on the web page for this episode. So again, Lance, really impactful work with important contributions to human health and medical care, and it's great that you're tapping into the potential of AI to help people know the status of their bones and potentially save lives. So thank you for taking some time to tell us today about this technology and development and to teach us about adaptable living smart bones that we all have.

LF: Thank you. This has been a pleasure.

And thank you to our listeners for learning along with us today. You can hear all of our Technology Today episodes, and see photos, and complete transcripts at podcast.swri.org. Remember to share our podcast and subscribe on your favorite podcast platform.

Want to see what else we're up to? Connect with Southwest Research Institute on Facebook, Instagram, X, LinkedIn, and YouTube. Check out the Technology Today Magazine at technologytoday.swri.org. And now is a great time to become an SwRI problem solver. Visit our career page at SwRI.jobs.

Ian McKinney and Bryan Ortiz are the podcast audio engineers and editors. I am producer and host, Lisa Peña.

Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SwRI bone and biomechanics research focuses on the fundamental understanding of the relationship between biological, mechanical and damage evolution behavior of biomaterials to quantify risk of failure and injury.

How to Listen

Listen on Apple Podcasts, or via the SoundCloud media player above.