Thomas Baker Slick, Jr., oil heir, business man, philanthropist, adventurer, author and inventor, impacted the world with his grand ideas and scientific pursuits. As we celebrate SwRI’s 75th anniversary, we remember the legendary and inspiring founder of the Institute who left a legacy of progress and innovation. Slick was known for his global vision and his desire to advance humankind. He was also known for his world travels, art collection and his expeditions in search of the mythical yeti. On this episode, his family members tell us they also knew another side of him, sharing intimate details of Tom Slick’s extraordinary life and their colorful memories of his humor and wisdom.

Listen now as Slick’s son, Chuck, and niece, Catherine Nixon Cooke, recall the man they knew as beloved father and uncle, and discuss how he continues to change the world today.

Visit History to learn about SwRI’s early years and expansion through the decades.

Transcript

Below is a transcript of the episode, modified for clarity.

Lisa Peña (LP): Seventy-five years ago, SwRI started with one man's vision. Our founder, Thomas Baker Slick, Jr., dreamed of a science city where advanced research and development would thrive. On this episode of Technology Today, Slick's son and niece share their stories and memories of the philanthropist, adventurer, and inventor who left a legacy of innovation.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

We live with technology, science, engineering, and the results of innovative research every day. Now, let's understand it better. You're listening to the Technology Today podcast presented by Southwest Research Institute. Transcripts and photos for this episode and all episodes are available at podcast.swri.org.

Hello and welcome to Technology Today. I'm Lisa Peña. 2022 marks Southwest Research Institute's 75th anniversary. Since 1947, SwRI scientists and engineers have made groundbreaking discoveries and developed transformative technology to benefit humankind. Today, we're learning about the man who launched it all. Southwest Research Institute founder Tom Slick was a businessman, philanthropist, adventurer, art collector, inventor, and more. But our two guests today knew him as beloved father and uncle.

Chuck Slick, son of Tom Slick, and Catherine Nixon Cooke, niece of Tom Slick and author of In Search of Tom Slick and Tom Slick, Mystery Hunter, are here to share their stories and memories of the larger-than-life, legendary founder of our institute. Welcome to the podcast and thank you both for being here.

Image Tom Slick Sr., “King of the Wildcatters,” reads to young Tom Slick, founder of SwRI, circa 1919. Early stories of adventure sparked Slick’s curiosity and imagination.Courtesy of Catherine Nixon Cooke

Tom Slick Sr., “King of the Wildcatters,” reads to young Tom Slick, founder of SwRI, circa 1919. Early stories of adventure sparked Slick’s curiosity and imagination.Courtesy of Catherine Nixon CookeTom Slick Sr., “King of the Wildcatters,” reads to young Tom Slick, founder of SwRI, circa 1919. Early stories of adventure sparked Slick’s curiosity and imagination.

Chuck Slick (CS): Thank you very much for having me.

Catherine Nixon Cooke (CNC): We're looking forward to being with you today.

LP: Well, this is really a special year for the Institute, as we celebrate 75 years. And what a great year to go back to our roots and learn about the man who planted the seeds for what we have become research and development, from deep sea to deep space, more than 3,000 employees, more than 1,500 acres at our home base in San Antonio, SwRI locations worldwide, including in China and the UK. So Catherine, I wanted to start with you. Will you give us a brief overview of Tom Slick's early life? What brought him to San Antonio?

CNC: A little family history is a great place to start. The first oil in the United States was discovered in Pennsylvania in 1859. And by the end of the 19th century, oil production was booming there. In 1899, a 16-year-old named Tom Slick left school in Clarion, Pennsylvania, headed for the oil fields, hoping for adventure and opportunity.

He worked on the rigs, and he eventually began prospecting himself. For a while, he was known as "Dry Hole Tom". That changed in 1912, when he discovered the giant Cushing Field in Oklahoma. And pretty soon, he had a new nickname, King of the Wildcatters. He married Berenice Frates, and they had three children. The oldest was the hero of today's podcast, Tom Slick Jr., born in 1916.

By 1930, Slick Sr. was the largest independent oil operator in the world, with beautiful homes in both Clarion, Pennsylvania, and Oklahoma City. But he was a workaholic, a chain smoker who often forgot to eat, always on the go. And he died at the young age of 46, when our Tom was just 14 years old.

With that background, on to answer your question about what brought Tom to San Antonio, a few years after Slick Sr.'s death, the widowed Berenice married Charles Urschel. They lived in Oklahoma City until 1934, when they moved to San Antonio for several reasons. Berenice's sister and her family lived in San Antonio, and many oil families moved to Texas in the 1930s because there was no state income tax.

There was also a darker reason. Charles Urschel had been kidnapped and held for ransom in Oklahoma by the notorious gangster Machine Gun Kelly. That's a story for another day. But the incident was traumatic for the whole family, and the move to San Antonio put those memories behind them.

They built a beautiful home right next to Berenice's sister's family. Tom attended Phillips Exeter Academy and graduated from Yale in 1938. As we know, he started establishing scientific institutes just three years later while still in his 20s, Texas Biomed in 1941 and Southwest Research Institute in 1947.

LP: Such a rich history. Thank you for that very thorough overview of Tom Slick's early life. And Chuck, I want to move to you now. I know you were so young when your father passed away. Were you 11 at the time? And what stands out to you? What do you remember most about the man behind the scientific pursuits?

CS: Yeah, that's true. I was 11 when my father died. And even more than that, my parents were divorced when I was five, and we moved to New Jersey with my mother. But my sister Patty and my brother Tom and myself would spend the entire summer in San Antonio with Dad. And that's when summer lasted all summer, unlike now. And so our time together was short, but it was intense. He was lots of fun. That's the main thing I remember.

But he did like to pass on parental wisdom through stories or sayings. One lesson he passed on to us was about courage, which he learned from his grandfather in the woods near Clarion, Pennsylvania, where the family still spent the summers. Apparently, in the woods outside their house, there was a big log over a creek that my father was afraid to climb over. But his grandfather told him, a coward dies 1,000 deaths, a brave man only one. He was very happy to express that to us whenever we were too afraid to do something.

Another thing he would use fairly often when we were kids and complained about being too hot or too cold when we were hunting, or when we were at a fancy restaurant and all we wanted was mac and cheese, was that you have to be adaptable, or you'll become extinct like the dinosaurs. And given his life, it seems that both of those things he really took them to heart.

He was never a big stickler for the rules. Cathy mentioned that he was at Yale. And while he was at Yale, he was the president of the Southern Club, which was supposedly for Yale students who were from the South. But he managed to get some of his best friends from Boston in the club, because he claimed they were from South Boston.

[CHUCKLING]

Image Courtesy of Catherine Nixon Cooke

Courtesy of Catherine Nixon CookeSlick and his children enjoying a boat ride in the Bahamas. Slick often traveled with his children, taking them on memorable vacations, left to right: Patty Slick, Chuck Slick, Tom Slick.

CS: He took us on lots of trips. We went to Bermuda. We went to the Bahamas, to Mexico, among many others. One summer, we drove from San Antonio to Los Angeles via the Grand Canyon. To make sure the trip was doable in the time before cars had air conditioning, my dad bought a Volkswagen bus from his stepbrother Charles Urschel's dealership and then had the engineers from Southwest Research Institute come attach a house air conditioner to the roof and pipe the cool air in. And so we were able to have a nice, comfortable drive all the way to Los Angeles.

[CHUCKLING]

CNC: I love that story.

LP: That's a great story.

[CHUCKLING]

Yeah, no, so you were so young when he passed. Yet, it sounds like he left you with so much wisdom, which speaks volumes about who he was. So we mentioned Tom Slick was an inventor. What would you say were his most memorable inventions?

CS: Well, his curiosity was boundless. Living in Texas, he had cattle. And he wondered if it would be possible to crossbreed Angus cattle, famous for their beef but not adapted to the Texas climate, with Brahma bulls, which, being from India, were able to withstand a hot, dry climate. And one of his foundations was a foundation for agricultural research, and they tried to do that. I don't know how successful they were.

The other main invention that stood out was what was called the lift-slab construction method, which was where you pour the concrete for a roof in a frame on the ground and then lift it up on top of the walls with a crane. I can't tell you why that would be a better process. But my daughter Anne, who's an architect, said the process is still used sometimes today.

I don't think either of the inventions or any other inventions specifically were terribly significant, but they were emblematic of someone who had an incessant curiosity. But differently for him than most of us, he would not only have an idea, but he would act on it.

And also, at some point, he created the Institute of Inventive Research, where they would take people's ideas, and if they were useful and patentable, they would get them patented and try and take them to market. But unfortunately, they were inundated with potential inventions. But apparently, none of them were particularly successful. So they eventually had to close the doors on that.

But I think the main thing is that his curiosity and his way of making action and creating something from his ideas is the fact of the various institutions, such as SwRI, Texas Biomedical Research, and the Mind Science Foundation and others. He felt many more questions would be answered and more achievements could be made if he created a structure for brilliant scientists and engineers to work and let them go to it.

CNC: I'd like to chime in about the lift-slab method of construction, which he developed with Philip Youtz. Quite a bit of lift-slab construction was used to build Trinity University in the San Antonio campus. And it was used mainly because it was a much less expensive construction process, which, in those days, meant a lot to a place like a university trying to build a beautiful campus as inexpensively but beautifully as possible. So that lift-slab method is still used a bit today, but it was used a lot more in the '50s and the '60s.

LP: And we still have examples of Tom Slick's lift-slab construction method here on the SwRI campus, which is neat to see. So it really is that spirit of innovation, that curiosity you talk about, Chuck, the reason that's the reason why we're here today.

And your father established a number of scientific research foundations, as you mentioned, including SwRI and our sister organization Texas Biomedical Research Institute, the Southwest Agricultural Institute, the Mind Science Foundation to investigate the human mind, the Human Progress Foundation to promote science education and peace, and others. What was his goal with establishing all of these various organizations?

CS: I would just say that, as I said before, is that he had these ideas that he thought he could he thought that human life could be improved by proven science and engineering, and if he created a structure for the scientists and engineers to flourish in, that that would be a great boon to humanity. And I would have to say, I think he was right, in that case, given all the success that Texas Biomed and SwRI have had, especially.

CNC: There's a direct quote from a letter that he wrote in 1952 that really backs up what Chuck is saying. And the quote is, "I would like to tell you how important the machinery of science is towards the future advancement of our civilization. Science gives us a tool of unparalleled effectiveness by which we can improve our lives, and since science recognizes no geographic boundaries, the lives of people all over the world." I love that global vision that he had for science. And I think it really captures what Chuck and you are both talking about.

LP: Yeah, he certainly looked beyond himself, beyond his region, and really wanted to change the world, which is still part of our mission today research and development to benefit all of humankind. And I love that quote you just mentioned, Catherine, this idea of science giving us the tools we need to improve our lives. So we mentioned Tom Slick was not only interested in scientific pursuits, but also a businessman. And while science was a priority for him, he also had other business interests. He cofounded Slick Airways. One of you tell us about his airline.

CS: Well, Slick Airways was mostly the project of Dad's brother Earl Slick, who was a brilliant businessman. Earl had been a pilot in the Second World War, and he knew that the Air Force had lots of surplus airplanes that could be bought cheaply. So they bought the surplus airplanes, and then they created a freight airlines in those days before FedEx and UPS. It grew to be the second largest freight carrier in the country until they sold it in the early 1960s. It was a big success. But the most interesting thing about it is that throughout my adult life, until fairly recently, at least, I would often run into people who had some connection with Slick Airways, a pilot, they were a pilot for Slick Airways. At one point, I ran into a woman who had been Earl Slick's secretary. And they would always say, oh, I remember the time at Slick Airways. And it was really meaningful to a lot of people. But it was a freight airline, because at the time, the regular airplanes carried almost no luggage or anything. And as I said, there was nothing like FedEx or UPS.

LP: So he was always looking for interesting business pursuits along with his scientific pursuits. And...

CS: That's true. I will say, that's true. He also they continued in the oil business and several other business interests. But Slick Airways was a big, successful one.

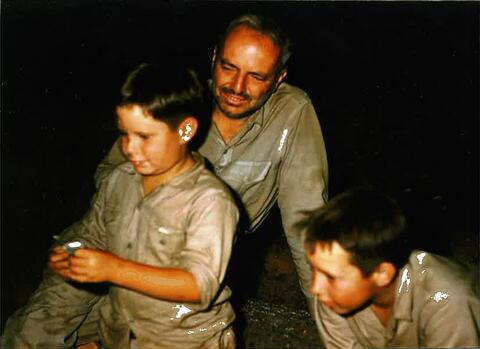

Image Courtesy of Catherine Nixon Cooke

Courtesy of Catherine Nixon CookeTom Slick and sons, Chuck (left) and Tom (right) search for Bigfoot in the Pacific Northwest, circa 1960.

LP: When you talk about Tom Slick, you have to discuss his search for the Yeti. The Yeti has become somewhat of a mascot here at the Institute. And you'll even see a life-sized metal Yeti cutout at random spots on our campus. We love moving it around. Tell us about his expeditions to Nepal and Tibet in search of the mythical creature.

CNC: Let me start with the Nepal expeditions. I researched them so thoroughly for the books. And then I know Chuck has got some great firsthand experiences to share with you as well. But from childhood, Tom Slick was really fascinated by undiscovered creatures.

His dad, when he wasn't out searching for oil, would tell his children wonderful stories about faraway places and exotic creatures. And that curiosity was really inflamed from the time he was little. And when he was in college, he searched for the Loch Ness Monster in Scotland with college fraternity brothers. And in 1938, just as he was graduating from Yale, a South African fisherman landed a coelacanth in their nets, thought to have vanished into extinction millions of years ago.

So there really was the thought, in the '40s and '50s and '60s, that there were these undiscovered creatures. And Tom Slick was certain that the Yeti was the undiscovered link. And he started looking for the Yeti, went on several expeditions in the early and mid and late 1950s to Nepal. I love the details of some of the Yeti expeditions. He shipped some bloodhounds over to Nepal for the trek and equipped them with their own small snow boots. He talked to several zoos and animal organizations and arranged to buy tranquilizer guns that he could take, because he explained, quote, "we don't want to kill this wonderful animal."

And then, of course, there's the story of smuggling the supposed Yeti thumb from the Pangboche Monastery high in the Himalayas to London, helped by actor Jimmy Stewart, who carried it in a film canister in order for a biologist in London to study it.

So there are just great dramas about those Himalayan expeditions. And all of us grew up, Chuck and his brother Tom and Patty and I, seeing the cast of the Yeti footprint on Tom's wonderful dining-room table in San Antonio, and having that right in the center of the table, and always lots of stories about how he found that footprint and remained convinced that there really was a Yeti or Bigfoot or Abominable Snowman. It was just a delight for us all during our childhood. And it continues to fascinate me today.

CS: Yeah, after sponsoring the Yeti expeditions in the Himalayas, Dad hired a small contingent to search for the Bigfoot in Northern California and the Sasquatch in British Columbia. And my brother Tom and I were able to go on that hunt, which was very exciting for us, as you can imagine, at the time, when I was about 10 years old. One night, there was apparently a Bigfoot sighting. The dogs got all excited and so on. But we never could find anything. I have to admit, though, that in my opinion now, there are more metal cutout Yetis on the SwRI campus than there are real ones in Nepal or the California mountains.

LP: [CHUCKLES] Yes, you can see one of those any day here. We love our Yetis, for sure. So you know I said mythical creature. That's how I describe the Yeti. But I liked how you said, Catherine, undiscovered creature. So what are your thoughts today on these creatures?

CNC: Absolutely. And the Yeti is such an important part of Nepal's identity. I think most people today agree with Chuck that, by now, there would have been bone or skull or something discovered if a Yeti really was roaming, or if Yetis were really roaming, the Himalayas.

But the myth of the Yeti has ventured into the culture of Nepal in all sorts of important ways. And there are museums, and there are books, and tourists come. And there are stories, and the lamas love to tell them. So the Yeti still plays a very real and important part in the life of the Nepalese people.

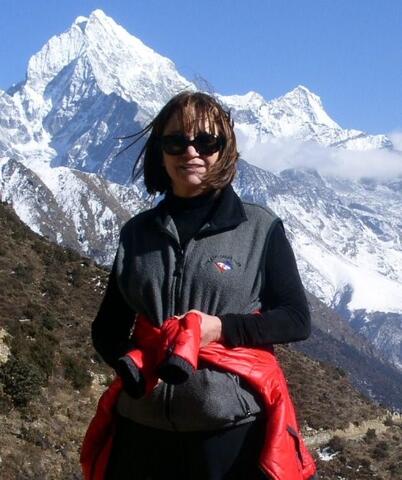

Image Courtesy of Catherine Nixon Cooke

Courtesy of Catherine Nixon CookeSlick’s niece, Catherine Nixon Cooke, re-traced Slick’s yeti expedition in Nepal in 2001 to research her biography of Tom Slick.

When I was researching the book, Tom Slick, Mystery Hunter, I did go with a group of six people tracing Tom Slick's footsteps on one of his expeditions. And we were very high in the Arun Valley of Nepal, and it was a tough trek. And we met some lamas who had been porters for Tom Slick back in the day very old men at the time. And they remembered him. They remembered the expeditions, and they still wanted to keep that mystery alive. I'll never forget the goosebumps of sitting around the campfire late at night, way up in the mountains, when a lama imitated the sounds of the Yeti that they had heard from afar. It was spooky. And of course, like Chuck said, we did not come across any Yetis. And I think that if there were some, modern science would have found evidence by now. But I believe in the magic of the Yeti. And of course, I still really enjoy stories about the Yeti and imagining what might have been. So I'm on the fence.

[CHUCKLING]

LP: OK. The magic of the Yeti is alive and well.

CNC: Right.

LP: So during his travels, Tom Slick met so many interesting people. You just mentioned actor Jimmy Stewart. But tell us about some of the influential people that he met along the way.

CNC: Well, they ranged from presidents to psychics, from religious leaders to movie stars, President Eisenhower, the Dalai Lama, psychic Peter Hurkos, Dr. Albert Schweitzer, CIA operative Jim Thompson, the Maharaja of Baroda, actress Rhonda Fleming, even Walt Disney that Chuck might tell you about.

I know these names because I was so fortunate, again, when researching the book, to have discovered his letters hidden away in an old shed at Texas Biomed. And so I was able to access the correspondence he had with these remarkable people over the years of his life. And I would open this up and say, oh my goodness, he's communicating with Albert Schweitzer in Africa.

So it was an eye-opener. And I love the story of the Dalai Lama, where he told the Dalai Lama that he was seeking consciousness, wanting to find that. And the Dalai Lama said, wonderful. How long do you have? Realizing that most people take a lifetime to find that. And Tom Slick supposedly said, I've got a week.

LP: [LAUGHS] Yeah, that's so great that you're able to hear him, hear his words in all he's left behind in his letters and in the quotes you mentioned. So that's great. Chuck, did you want to go ahead and tell us about Walt Disney? Because you actually met him as well. Is that correct?

CS: Well, yeah. This was the same trip when we drove with the VW bus with the air conditioner on top. And we went to Los Angeles. And when we were there, my father was great friends with a man named C.V. Wood, who was I think he was Walt Disney's director of real estate when he created Disneyland, the original Disneyland, in California. And my recollection and it could be a fond, made-up recollection. But my recollection was that Dad took he did take us to Disneyland. And I thought that my recollection is that we actually did go to meet Walt Disney himself in his office. And it was quite an event.

LP: What a life as you said, life event. [CHUCKLES]

CS: Yeah.

LP: That's a big one. OK, so we've heard about Tom Slick the businessman, the explorer, the science enthusiast. But he also loved art. Tell us about Tom Slick, the art collector. What were some of his most beloved pieces?

CS: Yeah, he was very interested in contemporary art. Now it would be called modern art, because [INAUDIBLE] more contemporary. But at the time, it was contemporary art. And it was mostly nonfigurative. But he also collected art from all the places he went to. He would buy paintings from the number-one painters in India when he went to India and various places. He bought paintings and sculptures from big auction houses in New York and Paris and London.

Image Courtesy of Catherine Nixon Cooke

Courtesy of Catherine Nixon CookeTom Slick in his living room with the Picasso painting that reminded him of his daughter, Patty.

He had, among his there was a wide variety of media. And among the artists in his collection were Picasso, Georgia O'Keeffe, Barbara Hepworth, William Baziotes, several others. And then there were several Texas artists that he had, including Charles Umlauf. There was an exhibition of his art collection at the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio in 2009.

But for his favorite pieces, I know his very favorite piece was a painting called the Portrait of Sylvette by Pablo Picasso, which he bought because the model in the painting of a young girl with a ponytail reminded him of my sister Patty. And then his second favorite was a really, really beautiful painting by Georgia O'Keeffe called From the Plains. And both of those paintings are in the permanent collection of the McNay Museum in San Antonio.

But he wasn't an art snob. When his brother Earl and his brother-in-law Lou Moorman, as a joke, gave him a finger painting by a chimpanzee named Betsy, saying it was just as good as his modern art, he laughed and put it on his wall. And that painting is now in the Chuck Slick permanent collection

LISA PENA: [CHUCKLING]

CS: my apartment.

LP: Yeah, I'm sure you found a special place for it.

CS: Absolutely. And also, one of the other reasons he liked that is that it connected two parts of his life, which is the primates that existed at Texas Biomedical Research Foundation, for their research, and the art world. So it was a combination. And he was very happy to have it.

CNC: And it also exemplified a really cute sense of humor that he had. I remember being at a dinner, Chuck, with all generations our parents, our age group. And he had this painting by Betsy on the wall with all these other great pieces of art. And after dinner, he asked the adults, many of whom didn't know much about art, to tell them what they thought. And they walked down the hall, picking out a sunset here or an ocean scene. And they got to the one painted by Betsy. And again, someone said, well, I think it's a lovely sunset or something like that. And I remember he just laughed. And of course, all of us children loved it because it was a gentle poking fun at the grownups. He had a really great sense of humor.

LP: Who had no idea it was painted by a monkey. [CHUCKLES]

[INTERPOSING VOICES]

LP: So from his art to another topic that was important to him, Tom Slick wrote two books on world peace. Why was this such an important topic for him?

CS: Well, it was during the Cold War. And I think the topic of world peace would naturally be of importance to someone with a curious mind and a penchant for taking actions regarding serious issues. He wrote those two books. He sponsored several major events where they would have world leaders. And I think they were mostly in Washington, but I'm not sure. And they would have secretary of state. And various people like that would come and try and how to create world peace.

That's a tall order. [CHUCKLES] And it never quite came to fruition, obviously. But it was in the later part of his life when the foundations were all on their own, standing on their own. Texas Biomed and SwRI, at the time, were standing he didn't need to be involved on a daily basis. And he was always interested in starting something new, a new project. And I guess there's no better project that you could come up with would be than world peace.

CNC: And I think he recognized its importance. Certainly, as Chuck said, diplomats and global leaders were beginning to recognize it. I know Eleanor Roosevelt had worked very hard for it in years before. But he also recognized the competitiveness of nations.

And I found some very interesting letters where he was concerned that the Russians were getting ahead of us in the space program. And he was corresponding regularly with the president, saying the United States needed to keep up. Remember Sputnik in 1957, I think. And they were ahead of us.

And I love that connection because it rolls back around to Southwest Research Institute and all of the work that the Institute does today in our developing space program. And I think he thought that our needing to be competitively ahead in technology was critical. And then at the same time, he recognized this need for nations to get along and hopefully work towards world peace.

LP: Yeah, I love that connection between world peace and science and, again, advancing humanity, as a whole. So we go back to his global vision there. So Catherine, as we mentioned, you have written books about your uncle. What motivated you to write about him? Why is his life a compelling topic for you? That's a funny question, considering all we've discussed. But what was that moment for you where you knew you just had to get this down and write about his life?

CNC: Well, I think I would really have to, first of all, thank Chuck's older brother Tom, my cousin, because when I first moved back to Texas from California in the 1980s, Tom encouraged me to help him run the Mind Science Foundation. This was Tom Slick's last foundation, established in 1958.

And Tom, my cousin, had really resuscitated it, because it only existed for four years before the Tom Slick we're talking about passed away. So young Tom, our Tom, my cousin, Chuck's brother, had been running it, resuscitating it, and convinced me, when I moved back to San Antonio, which is where it was based, to do that. And I ran that foundation for 15 years and loved it. And what an adventure. What interesting people I met.

And suddenly, I discovered other dimensions to a man I had known as a fun-loving uncle who drove us around in a toy Model T car remember that, Chuck? In the driveway and played. And suddenly, I found out more about him as an adult and what he had done for the world. I was also lucky because his siblings were still alive then. His aunt was still alive, Ramona Seeligson. They shared wonderful stories.

So when I retired from Mind Science Foundation in 1998, my next step was to write Tom Slick, Mystery Hunter. It was just a perfect way to pay tribute to this man that had changed certainly our city, certainly our world, and all of our lives in remarkable ways. So I published that. And then just last year, Texas A&M Press published a second edition called In Search of Tom Slick: Explorer and Visionary. And that was another wonderful process, more research.

And as I said earlier, discovering those papers and letters in the shed at what is now Texas Biomed, dated from 1947 until 1962, was like finding an incredible treasure. I was able to crawl inside the head of this remarkable man, because in those days, people wrote letters. No email, no... So there were reams and reams of letters that talked about everything from what kind of a pet he wanted to buy for his sweet little daughter Patty to what he was going to get Chuck for Christmas, then to these big things like correspondence with Dr. Albert Schweitzer or urging President Eisenhower to do more in the space missions.

Anyway, it was a very compelling topic, because it's not only an adventure story, but it's a salute to creative thinking, I think an encouragement to the reader to dare to explore and to question, to change the world, really.

LP: And change the world, he has. Sadly, Tom Slick died in a plane crash coming back from a hunting expedition in Canada in 1962 at 46 years old. How do you celebrate his life and keep his memory alive within your own family, and how does he continue to impact your lives today?

CS: Well, I think the best way we can celebrate his life is to continue to be involved with the institutions that he created. As Catherine said, my brother resuscitated the Mind Science Foundation. But my sister is now on the board there, as are several of Dad's great nieces and great nephews. And I'm on the board at Texas Biomedical Research Institute. And both my son Charles and I are advisory trustees at SwRI.

And I think we all feel like we should do whatever we can to make the world better, as he would have, but even though we can't do as much as he could or did. But as long as we keep the process going and the efforts going, I think that's the best way to celebrate his life.

Image

Chuck Slick, center, tours the SwRI Archives, with SwRI President and CEO Adam Hamilton and Institute Archivist Anissa Garcia. Historical SwRI documents, publications, images and pieces from Tom Slick’s art collection are preserved in Archives.

CNC: I totally agree with that. And another way that-- not as vibrant and long-lasting as what you just described, but in recent years, I've been fortunate to have written several books about San Antonio and its history. And in every one of them, I've been able to include the story of Tom Slick and the remarkable contributions he made to our city and beyond.

And coming out at the end of this year is a book that I co-authored with Henry Cisneros called San Antonio: City on a Mission. And it focuses on San Antonio's modern history. And so much of that history was influenced by Tom Slick. And Adam Hamilton plays a role in the book as well, the whole development of Southwest Research Institute.

And of course, my favorite hero is prominently featured in the book, as are all of the institutes he founded. You could say he really did create a science city, like he dreamed of all those years ago, in terms of San Antonio, which is now such a leader in biotechnology and science and research.

LP: And what would you like people to remember about Tom Slick?

CS: Well, I would like people to know that he was a fun father who always tried to make us better people. He was loving and caring to his children. And in all his travels around the world, he would always bring my sister Patty a new doll from each new destination. He cared for us, and it always showed. But more than that, he was always thinking of and doing things to make the world a better place, mostly by creating these enduring and successful institutions to use science to improve the human condition. And that's something to be remembered for. And that's what I would want people to remember.

CNC: I also love that another favorite quote the ones Chuck gave earlier were great, but there's another one that I think about almost every day. And it was simply this. There is no such thing as failure, only outcome.

LP: Again, so much wisdom there. Just an all-around great man. And thank you, Chuck, for giving us insight into what a great father he was as well. I love hearing about that side of him, too. So what do you think he would say about SwRI, Texas Biomed, and the Mind Science Foundation if he could see them today, all these years later?

CS: Oh, I think he would be extremely proud. The Mind Science Foundation makes a huge difference by studying the human mind and consciousness. Texas Biomed is one of the world leaders in the study of infectious diseases. They've been very involved in creating treatments for Zika disease, Ebola, AIDS, and in the creation of the COVID-19 vaccines. And SwRI is an incredibly diverse institution involved in projects ranging, as you all say in your tagline, from deep sea to deep space and everything in between.

One last aphorism that Dad liked I think he got it from the Navy Seabees. But it was, we do the difficult right away. The impossible takes a little longer. And I think the people at SwRI do the difficult and what used to be impossible on a daily basis and that Dad would be very, very pleased.

CNC: I think, too, that sense of enjoying the accomplishments would be evident. And I'm sure he would take my cousins and maybe I could tag along, too down in that deep submersible to the bottom of the sea.

I'm sure he would have his airplane-- have that paint removed by that brand-new largest industrial robot in the world that Southwest Research Institute developed. He'd be so proud of the vaccines and the brainstorm initiative supporting young neuroscientists in what he called the greatest frontier of all, the human mind. Chuck, don't you think he'd almost be like the proverbial kid in the candy store, delighting in the incredible progress of these recent decades?

CS: I really do. I really do.

LP: Well, thank you both for keeping up with all of our research and development. And I think we all want to make Tom Slick proud and keep doing what we're doing. So I think we're all better, and the world is certainly better because Tom Slick was here. So so much has grown from that first spark, Tom Slick's idea of a science city. And he is gone but never forgotten. His legacy and spirit live on with you, his family, and with us, the scientific institutes and communities at the organizations he created.

And to our listeners, if you want to know more about how Tom Slick's vision is a reality and changing the world with research and development, from deep sea to deep space, the now 45 episodes of this podcast are a great place to start. We cover it all. Well, thank you both, again, for sharing your cherished stories and memories of the inspiring and genius Tom Slick.

CS: Thank you for having me.

CNC: Thank you, Lisa.

And thank you to our listeners for learning along with us today. You can hear all of our Technology Today episodes and see photos and complete transcripts at podcast.swri.org. Remember to share our podcast and subscribe on your favorite podcast platform.

Want to see what else we're up to? Connect with Southwest Research Institute on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, and YouTube. Check out the Technology Today Magazine at technologytoday.swri.org. And now is a great time to become an SwRI problem solver. Visit our career page at SwRI.jobs.

Ian McKinney and Bryan Ortiz are the podcast audio engineers and editors. I am producer and host, Lisa Peña.

Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Thomas Baker Slick Jr. – an adventurer, philanthropist and oilman – founded SwRI on a South Texas ranch in 1947. After recruiting talent from across the nation, he challenged his team of scientists and engineers to seek revolutionary advancements through advanced science and applied technology. That spirit lives on today. SwRI endures as one of the oldest, independent nonprofit organizations in the United States, providing innovative science, technology, and engineering services to government and commercial clients around the world.

How to Listen

Listen on Apple Podcasts, or via the SoundCloud media player above.