Background

Since the early 1990’s, commercial vehicles have suffered from repeated vulnerability exploitations that resulted in a need for improved automotive cybersecurity. This research describes the strategies and challenges involved in securing vehicle networks through the implementation of an automotive Zero Trust Architecture (ZTA). The concept of Zero Trust asserts that a device must never assume that communication is trustworthy, regardless of the source or location within the network, following the IT principle of “never trust, always verify”. This research focused on drastically improving security of the cyber physical vehicle network with minimal impact to performance, measured as timing, bandwidth, and processing power.

Approach

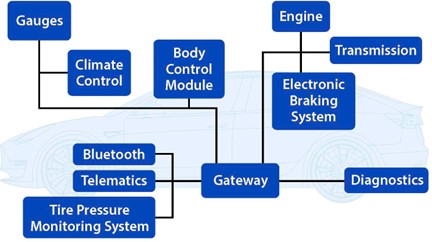

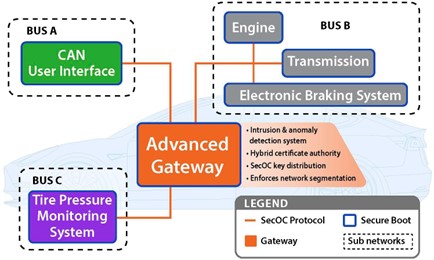

The automotive ZTA was tested using a software-in-the-loop vehicle simulation paired with resource constrained hardware that closely emulated a production vehicle network. This ZTA solution leverages the best cybersecurity practices from the IT industry and preexisting vehicle architecture components. For example, the vehicle gateway electronic control unit (ECU) is utilized to enforce cyber policy, monitor the network, distribute keys, and implement network segmentation. Other applied security solutions include Secure Onboard Communication (SecOC) for authentication and verification of network communication and Secure Boot to ensure the system is running authentic software. Implementing these elements and the other security controls is complicated by cost, resource constraints, and the complexity of building and maintaining vehicles.

Figure 1: Traditional vehicle architecture.

This research successfully implements the Secure Onboard Communication Protocol, Secure Boot, ECU authentication, key creation and distribution, and a network monitoring system. The Zero Trust Architecture concept has been successfully demonstrated through a software-in-the-loop vehicle simulation utilizing Raspberry Pi’s and automotive grade ECUs as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: IR&D zero trust vehicle architecture simulation.

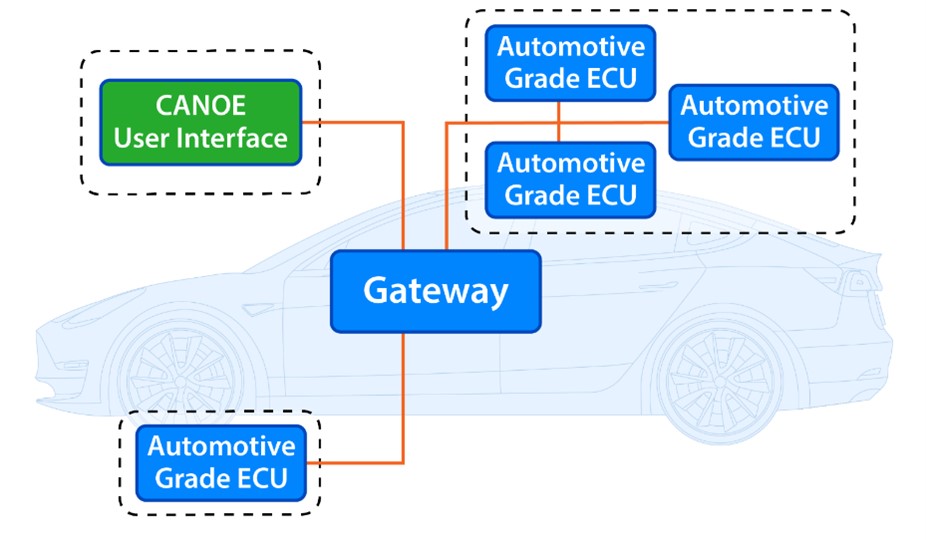

The simulation was adapted to a higher fidelity model that included hardware comparable to that seen within a fielded vehicle as shown in Figure 3. The research team (Figure 4) encountered obstacles when integrating security components within the resource constrained automotive environment including: latency during the MAC generation and verification process, latency during the key distribution process, secure storage, latency executing Secure Boot, and latency executing SecOC verification. These challenges and restrictions stem from the limited hardware resources within an automotive ECU. Exchanging the Raspberry Pis with automotive grade processors presented additional constraints for cryptographic operations as well. The hardware resources on the automotive ECU were not powerful enough to implement Zero Trust measures with an acceptable amount of latency. To combat this problem, a hardware security module (HSM) was utilized as an extension to the ECU. This module contains secure data storage and a cryptographic accelerator for fast execution. The HSM was used for the dynamic key distribution, SecOC protocol, and Secure Boot components of Zero Trust.

Figure 3: Automotive ZTA simulation with automotive ECUs.

Accomplishments

The project team recognized that to comply with current vehicle standards, a set of target metrics must be developed. These metrics ensured the ZTA was functioning as expected and additional latency from components did not limit vehicle operations. The target metrics included: Error monitoring system detects 100% of illicit messages; ECUs refuse unauthorized firmware 100% of the time; ECUs discard unauthenticated messages 100% of the time; and latency at first ignition cycle was less than one second.

These requirements outline a measure of success for implementing a ZTA within an automotive network. The collected data demonstrated the feasibility of implanting ZTA within automotive networks and were explored during project testing. The results of these tests demonstrated that the simulation was able to detect 100% of the malicious messages sent by the attacker device. Furthermore, none of the malicious messages were accepted by any ECU, allowing the system to remain fully functional during the attacks. This achievement validates the fulfillment of target metrics one and three.

Ultimately, the project team’s primary concern in testing requirements one and three was to identify that an error had occurred, rather than identifying which type of error occurred. However, it is still valuable to assess how the system labeled errors and attacks. Based on data gathered through vulnerability testing, the ZTA’s labeling of errors was not always accurate and heavily depended on the type of error or simulated attack being performed. For example, during vulnerability testing, fuzzing and spoofing had close to 100% accuracy of being labeled correctly. However, classifying the replay vulnerability resulted in 0% accuracy for timed replays and 100% accuracy for synchronization replays. Yet, malicious messages were detected regardless of the identification label generated by the ZTA. During vulnerability testing of the Secure Boot system, on the Raspberry Pi, the bootloader refused to load unauthorized firmware 100% of the time. The device successfully booted only after the boot firmware was correctly signed with the developer’s private key, ensuring the protection of the connected vehicle hardware. The results from testing the Secure Boot system validate the fulfillment of target metric two.

Lastly, target metric four was assessed through the key distribution latency performance testing. However, this requirement was only fulfilled by the low fidelity simulated vehicle network consisting of Raspberry Pis. The low fidelity model presented a latency at startup of less than 1.0 seconds with a time of 0.212 seconds. This initial result was anticipated due to the increased computation power of the devices utilized in the simulation. When testing the higher fidelity model, consisting of automotive grade ECUs, target metric four was not successfully met. With the key distribution latency timing equating to vehicle startup latency, the higher fidelity model presented a timing of 1.933 seconds. Therefore, additional resources are needed to meet the 1.0 seconds requirement using automotive ECUs.

This research presents a proof-of-concept for the implementation of a ZTA within a simulated vehicle network. Throughout the report the design choices were correlated to industry best practice guidance for the deployment of an enterprise ZTA solution as presented in CISA’s Zero Trust Maturity Model. The project team highlighted enhancements to automotive network security through an implementation of SecOC, Secure Boot, and key distribution. Additionally, the ZTA leveraged an Advanced Gateway to enforce cyber policy, network monitoring, and network segmentation. The metrics collected yielded favorable results indicating ZT principles in an on-vehicle network greatly improves the cybersecurity posture with manageable impact to system performance.

Vulnerability testing revealed similar performance between the Raspberry Pi and automotive ECU. The developed software was configured to run on both platforms with no unexpected deviation in behavior or functionality. However, during latency tests the automotive ECU demonstrated inferior performance in comparison to the Raspberry Pi, primarily due to limited hardware resources. Most notable timing differences were attributed to computationally intensive cryptographic operations. Through further investigation, it was determined that the automotive ECU alone could not effectively support a ZTA implementation due to these hardware limitations. A solution found in this research was to pair lightweight embedded systems with an HSM. The HSM accelerates cryptographic processes to speed up execution time, while securely storing sensitive data such as encryption keys. This combination addresses the performance bottlenecks and ensures that the cryptographic requirements of a ZTA can be met without compromising security or efficiency. Ultimately, an automotive ZTA is feasible and offers numerous security advantages that should be further explored.

Figure 4: ZTA research project team.